Sometimes Claire sees their attacker walking around on campus.

In those moments, Claire said they feel as though their legs turn to jelly, as if they might die.

It’s then that Claire seeks refuge on the ground floor of the University of Maryland Health Center, in the CARE to Stop Violence office.

“CARE literally saved my life,” said Claire, a graduate student who uses they/them pronouns and is being identified by a pseudonym to protect their identity as a survivor of sexual violence. “After I was raped, I didn’t know what to do or who to talk to, and it was really hard to trust people, too. But the people at CARE are really warm and inclusive and supportive.”

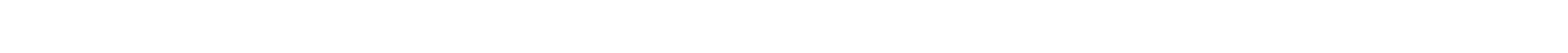

The CARE office counsels hundreds of students affected by sexual assault and trains thousands more in how to prevent this kind of violence before it happens. The office, which has eight staff members, is dependent on grant funding to fulfill its work.

While CARE’s portfolio of responsibilities has grown in recent years, the office is historically underfunded and relies on grant awards that expire after one to three years, said assistant director Fatima Taylor.

From 2015 through 2016, CARE scheduled about 650 therapy visits for students, and provided first-time consultations to 117 new clients. On a campus where statistics predict one in five women will be sexually assaulted, CARE is the only confidential resource specifically for victims of sexual violence.

Other counseling resources on the campus impose a limit on the number of free, one-on-one sessions a student can have per year, but CARE has no strict policy. Though counseling is typically short-term, Claire has been seeking help from CARE for more than five years.

The office helps students who have experienced sexual violence access medical care and provides transportation if they need to go off the campus to get it. It aids survivors in securing legal assistance, if that’s the route they take. And it supplies academic support letters to alert professors that a student might need accommodations with assignments.

CARE also takes a lead on campus sexual assault prevention efforts, bringing bystander intervention training to all UNIV100 classes and other campus organizations.

University President Wallace Loh recently accepted recommendations from the Joint President/Senate Assault Prevention Task Force calling for additional prevention training for campus community members.

The “biggest change in the whole program” is mandated in-person bystander intervention training for all freshmen, Freshmen Connection students and transfer students, said the task force’s chair Steve Petkas. This means the university would train more than 8,000 students in their first year, compared to the about 3,600 trained last fall.

“In order to meet the recommendations of that document, we likely will need to somehow find more staff,” said Health Center Director David McBride, who oversees the CARE office. “Just to train those additional bodies, we will need to find more folks to do that.”

If a student tells a professor, resident assistant or university employee about an incident of sexual misconduct, that official is most likely required to report the disclosure to the Title IX office. University officials recommend employees direct students to CARE if they want to disclose confidentially.

Title IX Officer Catherine Carroll called the office “one of the most important resources on our campus.”

By the numbers

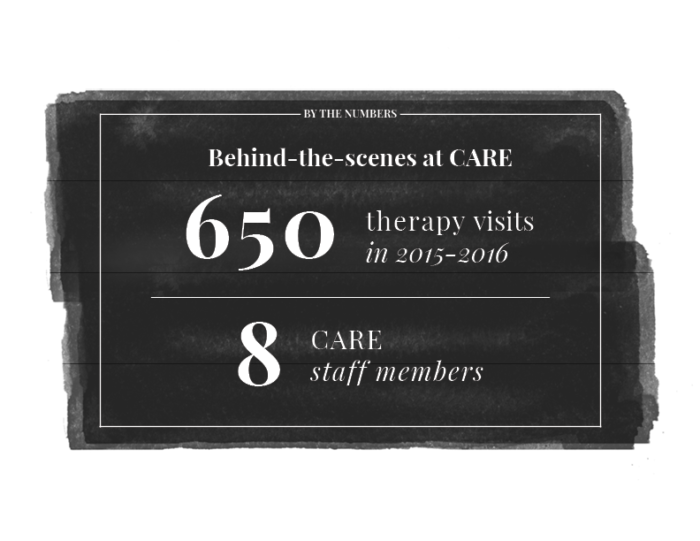

CARE has a $500,000 annual budget composed of state and federal funds, student fees and grants, with 95 percent of that money going toward staffing, according to university communications. There are seven full-time staff and one part-timer working at CARE, which Taylor said is the largest the office staff has been.

But half of those eight staff members are funded through state and federal grants, which last between one and three years.

“I’d like to see CARE more permanently funded because I think that it’s invaluable to our students and there are real good people there who will help students through these kinds of situations,” said Andrea Goodwin, this university’s student conduct director. “I hope that we are going to be able to find some more money to put toward the CARE office.”

The office’s work is bolstered by a team of interns, Peer Advocates and Peer Educators. These students also counsel survivors, lead workshops on bystander intervention and man a crisis cellphone 24/7.

Under the current funding structure, staff must regularly devote time to seeking out and applying for grants, and there is less job security for the people whose salaries are tied to a grant.

A few years ago, Taylor said, a part-time staff member had to leave the office after the funding used to pay for their position dried up. That person was tasked with outreach, specifically for “hard-to-reach” groups.

“If you want to retain good people, and you want them to stay, you want to make sure they’re permanent,” Taylor said. “As soon as you get someone here, you have to think about re-upping [the grant].”

The CARE to Stop Violence center in the Health Center in this file photo taken September 24, 2016.

CARE currently manages three grants, and two will expire this year.

A three-year, $580,000 award from the justice department’s Office on Violence Against Women ends in September. CARE is seeking a no-cost extension, meaning there are still leftover grant dollars that the office hopes to use after the award period ends.

The grant, which was awarded in 2014, has been used to fund staffing needs.

“We’ve tried to establish some contingency funding within our budget in the event that we don’t have that continuation,” McBride said. “I’m hopeful that we wouldn’t have to eliminate any position, but at this point, our budget is really just in the process of being submitted so I can’t say for sure. … The Health Center has historically done a lot of moving funds around in order to try and maintain services of core importance.”

This university was one of more than a dozen schools to receive money through the justice department’s Grants to Reduce Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence and Stalking on Campus Program in 2014, in amounts ranging from $299,004 to $580,000.

Now, many of these schools are in similar positions. At Northwestern University, students submitted a petition earlier this year that demanded, among other things, permanent funding from the university for the Coordinator of Men’s Engagement position within the Center for Awareness, Response and Education office. Students expressed concern about the future of that position now that the federal funding that pays for it is set to expire.

Financial support for CARE also comes from the Maryland Governor’s Office of Crime Control & Prevention. Since 2014, the agency has awarded four grants to CARE for “salary support,” totaling nearly $400,000.

CARE is in the middle of a two-year, $287,027 grant from the governor’s office, which kicked in Oct. 1, 2016 and runs through Sept. 30, 2018. This grant pays for a therapist advocate, an outreach-education coordinator and some training and victim assistance funds, said Laurie Rajala, chief of programs in the Governor’s Office of Crime Control & Prevention.

This university would have to reapply for the grant in 2018, Rajala said, and would be “competitively reviewed and scored” to determine if it’s funded for another cycle.

The third grant CARE manages goes toward translating office materials into other languages, according to university communications.

This university’s CARE office is cognizant of the uncertainty in the political arena, where federal resources for sexual violence have recently been threatened.

“If all the grants go away — or the national climate related to this issue changes and that goes — that’s what happens to our office,” Taylor said.

Parts of the puzzle

The way the University of Maryland spends money on combating sexual assault garnered national attention this year after the Student Government Association voted in September to support a $34 mandatory student fee to generate funds for the Title IX office.

Since its creation in 2014, Carroll had repeatedly said her office is understaffed and underfunded. Resolution of sexual misconduct complaints took twice as long as the recommended 60 business days during the 2015-2016 academic year, according to the office’s annual report.

The university invests about $2 million a year to prevent and investigate sexual misconduct across campus, according to university communications.

Recently elected SGA President A.J. Pruitt, who championed the Title IX fee before it was eventually withdrawn, said he didn’t want students to foot the bill. He hoped the proposed fee would generate enough focused attention to push the administration into devoting more funds to the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct.

About a month after the SGA voted to support the fee, the university announced it approved six new positions across campus to address sexual misconduct issues.

This included four in the Title IX office: a deputy director, two sexual misconduct investigators and a standing review committee coordinator.

The statement also included that “two new positions have been approved for the CARE to Stop Violence office in the University Health Center to increase counseling and outreach efforts.”

This did not represent new funding from the university. These two CARE positions were funded by the Governor’s Office grant Taylor had applied for.

“I was a little disappointed at the wording of the university statement when they announced these hirings because it made it sound like they themselves out of their operating budget were setting aside funds for this purpose,” Pruitt said.

Pruitt said he understands this university doesn’t have infinite funds, and must utilize grants to bolster its work. But he said he’s nervous about having vital positions, like those at CARE, reliant on temporary dollars.

“We can’t get to the end of that cycle and that money and just let go of these positions,” he said.

Taylor said it’s key all groups involved in sexual assault prevention are fully funded, as they are working toward the same goal.

“If [Title IX] is getting more clients, they’re going to want to be doing referrals [to CARE] and vice versa,” she said. “If a lot of people are coming in here and there’s this uptick in people wanting to report, we have to make sure other people are ready to receive those reports. We can’t have any weak links in the whole puzzle.”