Alleged sexual assault occurs

Blair reports the alleged assault to the Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct (Title IX)

The Title IX office completes its draft investigation report and allows both parties to review it during a 5-day period.

This marks 60 business days. If the university met its time goal time frame, Blair’s case would be resolved.

The Title IX office’s final investigation report finds Blair’s alleged attacker responsible for Sexual Assault I and II.

The Standing Review Committee agrees he is responsible for Sexual Assault I and II.

Student Conduct Directory Andrea Goodwin notifies Blair that her alleged attacker is suspended.

Blair and her roommates were scanning the aisles of IKEA for a living room rug and other decor to furnish their new Commons apartment. Suddenly, Blair’s breath became labored, and her head started to spin.

She rushed to the store’s bathroom and heaved. Kneeling over the toilet, she knew this wasn’t normal. A few hours ago she told her roommates what happened the night before. “Someone forced himself inside of me,” she recalls saying.

In the ensuing weeks, these panic attacks came more often. It took her two weeks to say the word “rape,” and after three months, she still hadn’t told her mom. Simple tasks drained her to the point of exhaustion. She lost 20 pounds in one month. She missed classes.

It took almost three months before Blair filed a complaint with the University of Maryland’s Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct on Nov. 23, 2015. After combing through the university procedures, she anticipated the process would take no longer than the recommended 60 business days.

What she didn’t know was that the office’s director had publicly expressed the need for more funding to adequately investigate sexual misconduct cases. About two weeks before Blair filed her report, The Diamondback’s editorial board urged the administration to devote more resources to the office.

Blair’s case would drag on for eight months.

“That fall semester was hell,” said Blair, a senior government and politics major who agreed to be identified by this pseudonym. The Diamondback does not generally identify victims of alleged sex crimes.

While the office’s policy tries to adhere to a 60-day time frame, Student Conduct Director Andrea Goodwin said she and other officials, deeming it unrealistic, may need to revise it.

“We probably as a university need to either amend the policy to say that we are not going to be able to meet that 60 days, or we’re going to need to look at ways where we can reduce the amount of time in the process,” Goodwin said.

Coming forward

Irritable, paranoid and overwhelmed, Blair lashed out at friends and loved ones in the weeks after the alleged assault. She developed canker sores in her mouth from the stress. Once a frequenter of the then-Interfraternity Council tailgates and the off-campus bars, she began to withdraw out of fear of crossing his path.

Blair’s friend Gavri Schreiber said she became an alien version of her former self.

“Beforehand, she was just very bubbly, very smiley and very friendly,” said Schreiber, a senior philosophy major. “She did such a 180 in personality.”

One day, lying alone in bed, she scrolled through her Facebook feed and came across a newly posted picture of her alleged attacker, smiling and laughing with friends. She didn’t think it was fair that while she now struggled with depression and anxiety and couldn’t sleep through the night, his life seemed to go on as normal.

It was then she decided to channel her rage, her depression, her anxiety into action.

“It was easier for me to be angry than to dive into some of the more vulnerable and scary emotions,” she said. “Like being traumatized and being a victim and feeling helpless and exposed and that sort of stuff. Hardening and being angry was just easier.”

Blair read the university procedures over and over and thought she knew what she was getting into by reporting to Title IX. At the most basic level, the process for resolving a sexual misconduct complaint includes three steps: The Title IX office completes its investigation, a review committee hearing occurs and the Office of Student Conduct makes a disciplinary decision.

Blair’s case was one of the 26 investigations completed by the university’s Title IX office in the 2015-2016 school year.

A record number of seven students have been expelled for Sexual Assault I in the two academic years since this university established its Office of Civil Rights and Sexual Misconduct in 2014. This came as part of a national rush of colleges aiming to comply with former President Barack Obama administration’s new guidelines for addressing campus sexual assault.

But on a campus of more than 53,000 students, faculty and staff, the Title IX office has struggled to find its footing since its establishment. An overload of cases and requirements left Blair in the dark, at times, about her own case.

Blair thought reporting would bring her some justice, and while the reporting process provided her with a voice, it was more trying than she expected and lasted 152 business days.

Resolutions of sexual misconduct complaints at this university took twice as long as the recommended time frame during the 2015-2016 academic year, according to the office’s annual report. This university is one of 238 schools under federal investigations for its handling of these cases.

“We generally lack, and still do to a large extent, the significant infrastructure needed to address these issues and to respond effectively and promptly as we’re required to do under Title IX,” Title IX Officer Catherine Carroll said at an October University Senate meeting. “We’re building the ship as we’re driving the ship.”

Investigating sexual misconduct cases at the university level brings additional challenges not seen in a court of law, such as working around school breaks and relying on witnesses to respond to interview requests. This, along with other challenges, makes it more difficult for this university to meet the 60-day time frame for completing a case.

And even after the university announced it was adding four more positions to the Title IX office, Carroll echoed that sentiment when speaking to students protesting on McKeldin Mall in April.

“It’s just a lot to build in a very short amount of time,” Carroll told a group of students gathered to rally against sexual assault. “… You’re developing it while you’re doing it.”

Turning pain to power

Each of the tabs on Blair’s internet browser was opened to a different definition of rape. Reading the state’s definition and the university’s policy, she tried to make sense of what happened to her the night at the start of her junior year.

“The fact that I didn’t have a black eye or broken wrist was invalidating to me, like I didn’t deserve to call it rape,” she said. So Blair kept Googling definitions, reading blogs and searching the internet for an answer to how she should be feeling throughout the first few months after the alleged sexual assault.

During those eight months, Blair continuously sent emails to campus officials about her case and reviewed pages of documents describing what happened. Each update dragged her back to a night she so desperately wanted to forget.

After 47 business days — 13 days before the goal time frame for completing the entire process — the Title IX office hadn’t finished the initial investigation.

But by this time, Blair was able to review the draft report, the first material she read since reporting to the university three months prior. This meant she had to read, in blunt language, a description of her alleged sexual assault.

It was the first week of her junior year and Blair blasted music in her Commons apartment, singing and dancing with her roommates as they got ready for a night out in College Park.

When LMNT’s “Hey Juliet” played, Blair remembers singing along as she pulled her phone out to take a video of herself over Snapchat. This video, branded with the Commons apartments geotag at the bottom, would ultimately serve as evidence of her whereabouts in the university investigation into her alleged sexual assault.

Like most survivors of sexual assault, Blair knew her alleged attacker. He had lived on her floor her freshman year, and she said he was a trusted friend. The night of the incident, Blair said he sexually assaulted her at his off-campus house.

And now, almost six months since that night, she was reviewing a report in which her alleged attacker claims they never had sex. He is quoted recalling that Blair looked at him with “googly eyes.”

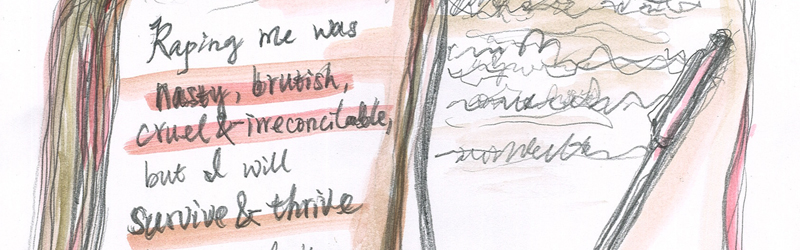

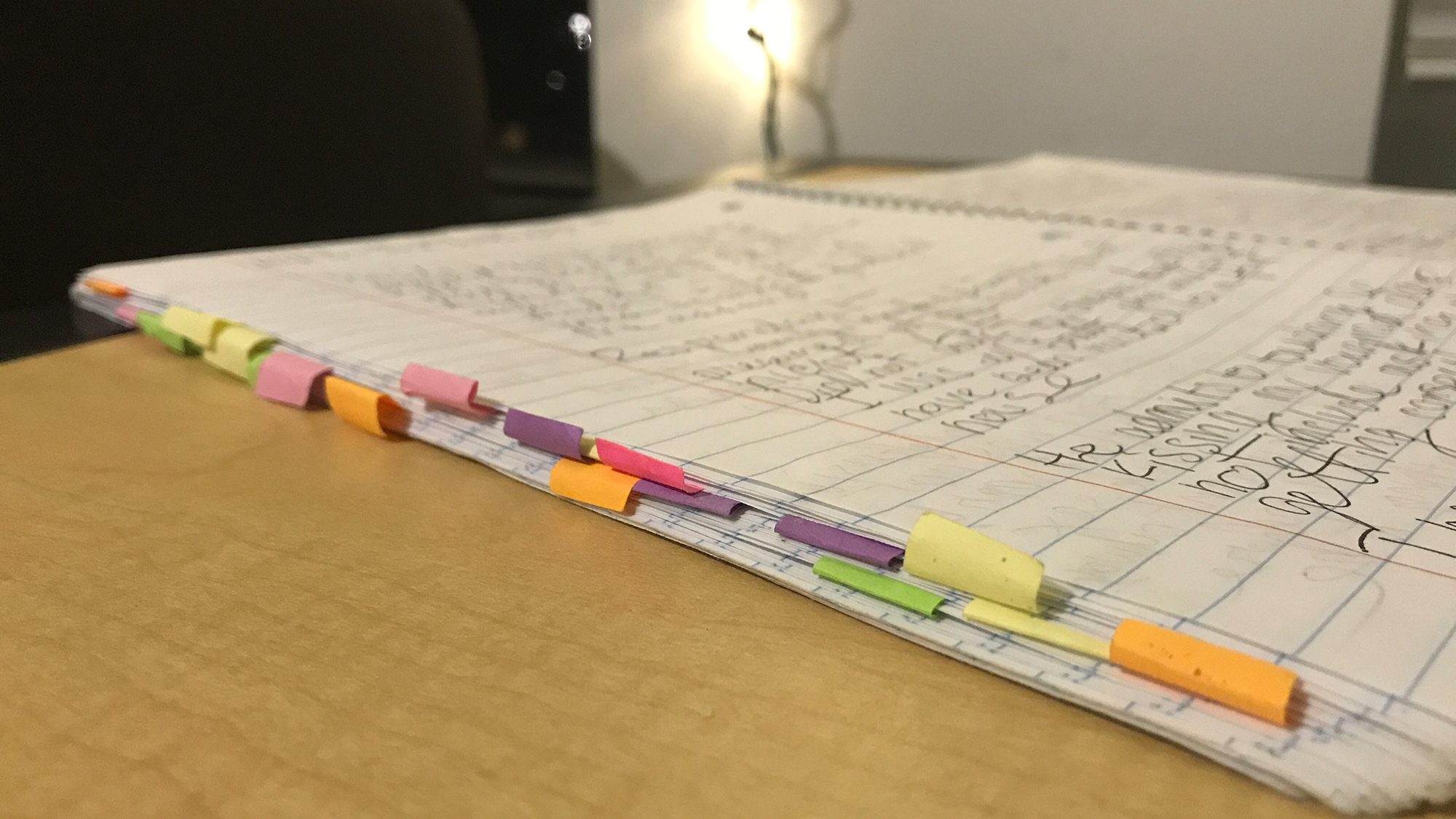

Blair wrote every detail she disputed in a spiral notebook, including the page and paragraph number of his statement in the draft investigation report. She turned her notes into a formal response to his claims.

“Everything that he said made me livid,” Blair said

She still had 105 business days to go.

Blair journaled throughout the entire reporting process and wrote down the claims she disputed in this spiral notebook. (Hallie Miller/The Diamondback)

Kept in the dark

March 1, 2016 — It had now been five days since Blair submitted her response to the draft report and it was all she could think about during her overnight shift at work.

What did the investigators think of it? What did he write as his response? What would happen next?

She spent the entire shift searching for previous Title IX cases online and researching resources offered by End Rape on Campus. She read the university’s policies and procedures over and over and over again.

By 5:33 a.m., she’d had enough of her own uncertainty.

She emailed her case’s investigator to ask what the next steps were. The investigator replied that before the review committee hearing, the lawyers in this university’s Office of General Counsel would be reviewing her report. Blair was not told exactly how long this would take.

The University System of Maryland’s sexual misconduct policy requires that the Office of General Counsel look over these kinds of reports to ensure the office is following through with its process as outlined in official guidelines. But because this university’s policies and procedures do not include this step, Blair felt confused.

“I do not want to be caught completely off guard and on the other hand I do not want to be anxiously refreshing my email every moment waiting for something that is a long ways away,” Blair wrote to the investigator on March 9. “I would appreciate any generalization, timeframes, or insight you may be able to provide.”

The investigator replied that it would be “difficult to estimate,” but her “general guess would be sometime shortly after spring break.” Three weeks later, another investigator confirmed to Blair via email that her case’s report was still with the Office of General Counsel, but could not provide her with any more details at that time.

Blair said she didn’t understand why lawyers were reviewing the report, why they couldn’t give her more information and why she felt so out of the loop in a process she thought would empower her.

“I felt so powerless,” Blair said. “The longer you have to think about something, the more complex the thoughts get, the more your head spins and ideas get twisted, and you think about the worst possible case scenario. … And in this case, the worst possible case scenario was super plausible.”

Carroll said the Title IX office values “quality and thoroughness over promptness.” With more staff, she thinks they could reduce the timeline.

“The process itself is always going to be difficult, so we do our best to be sensitive about that,” she said. “So that’s why we do our best to keep people informed and connect them with resources.”

Blair said she lived on edge in a constant state of uncertainty, worry and panic as her own timeline dragged on.

Consumed by the weight of the investigation, Blair rushed out of class on April 4 and had a panic attack in the health center.

A few hours later, she received an email from the Title IX office. After 76 business days, the investigation report was completed. It found him responsible for both Sexual Assault I and II, non-consensual penetration and touching.

But the report’s conclusion didn’t dissolve Blair’s anxiety as she expected.

“It didn’t fix everything that was wrong inside,” she said. “The damage was already done.”

Seeking justice

On April 29, more than five months after she reported, Blair walked into the same room as her alleged attacker.

Following this university’s due process standards, a conduct board composed of a mix of five trained students, staff and faculty members met to hear the case after the Title IX office completed its investigation report. Blair was told that even though it might be hard for her to hear, it was in her best interest to be present.

Blair sat in a narrow conference room on the second floor of the Mitchell Building. They brought him in first so she didn’t have to pass by him. She requested to sit near the door.

She recalls thinking that the room should have more exits.

Being in the same room as him was terrifying, but “I wanted to feel like I did absolutely everything I could to make myself feel safe and get him the hell out of here because he was making this university a worse place,” she said. “And I wanted him to know he didn’t get to push me around anymore.”

When it was his turn to speak, Blair started to cry. She had hoped to appear stoic, but the sound of his voice was too much to bear. Still, she refused to leave the room.

A week later, the committee found him responsible for Sexual Assault I and II. He appealed the decision, complaining that there was gender bias because only one male sat on the committee. He claimed the trial was not handled fairly, and he sought to respond to additional testimony.

His appeal was granted.

On June 30, the same Standing Review Committee found him responsible again. Neither party was allowed to be present that time. Blair read in an email that Goodwin recommended dismissal from the university. At first, she felt a sense of triumph.

But after double-checking online to see what exactly “dismissal” meant, Blair found that it could mean either expulsion or suspension. She sent an email to Goodwin to clarify.

Blair got her answer on July 7. Goodwin said Blair’s attacker was suspended for two years and could reapply after that time frame expired.

In determining sanctions, Goodwin said she considers a student’s remorse and any steps the respondent has already taken to remedy the situation.

“If somebody admits responsibility, I work with that student so that they aren’t permanently dismissed, so that they could be suspended,” Goodwin said. “It really depends on the circumstances of the case.”

The decision shook Blair. She didn’t understand how someone could be found responsible for two counts of sexual assault, deny it, and not be expelled.

The next day, Blair appealed the decision and motioned for him to be fully expelled. He also appealed the decision, hoping to complete his courses online without having to reapply after two years. The appeals were considered by a separate body, which upheld the two-year suspension.

Blair’s friend Morgan Benner, a senior psychology major, accompanied her to the Title IX office the day she received the news of the final decision.

“She was in a bad place,” Benner said. “She was pretty inconsolable.”

‘My rape does not define me’

Blair spent most of her junior year wondering if she would ever make it out of bed again. Through the thin Commons walls, she would often hear her friends and roommates laughing in the living room.

Now, 21 months after the alleged attack, she’s found the strength to sit and laugh with them. It’s hard for her to believe she graduates this month — a milestone that, on her darkest days, she doubted she could reach.

Her friends say they notice the improvement.

“She doesn’t have to live through it every single day as much anymore,” said friend Akhil Uppalapati, a junior government and politics major. “It just took way too long, and it was very re-traumatizing for her.”

Blair held an internship this semester, in which she worked with refugees. She also spends time volunteering and hanging out with friends.

“My rape does not define me, but it sure as hell does define him,” she said. “The resilience is what I should move forward with instead of the trauma.”

The anger is still there, often manifesting itself as biting sarcasm and bitterness when she speaks of the school that she thought would do more to empower her.

“I have less respect and less pride to be part of an institution who can act, like, so manipulative and deceitful,” she said. “And it just all seems very two-faced, like they want the best for their students until it’s not convenient for them.”

What began as a mission to bring down her alleged attacker evolved into a campaign against this university. In September 2016, Blair filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education. Her case, opened on March 31, is one of two active cases against this university.

“We as an institution are absolutely committed to responding to sexual misconduct, sexual assault — to preventing them, to providing training and counseling — and we have made available the resources that are needed,” university President Wallace Loh told The Diamondback in October in response to the student efforts to increase funding for the Title IX office.

Saskia Matthews, an alumnus whose own complaint against the university was not opened by the U.S. Education Department, filed her complaint at the same time as Blair. She said her own experience with the administration closely mirrored her friend’s.

“Something I really didn’t appreciate was just feeling that you had to fight for any respect from the Title IX office,” Matthews said. “You’re in a constant fight with the school to take you seriously. They don’t recognize it as the epidemic that it actually is.”

Anna Voremberg, End Rape on Campus’ managing director, said schools across the country often face non-compliance with Title IX guidelines.

“It’s up to the high-level administration, as well as the trustees, to ensure that the Title IX office has funding, to complete investigations in a timely manner that are also high-quality,” she said.

Matthews said she marvels at Blair’s ability to have made it through the process essentially on her own and display the ferocity that the process demanded.

“If I weren’t such a bitch,” Blair said, “it wouldn’t be over.”

On average, it takes the Department of Education 1,469 days to complete its investigations.

The Diamondback reported this story over four months, during which reporters spent more than 20 hours with Blair discussing her case. The reporters sat with Blair in her apartment as they reviewed emails, official documentation, class syllabi, her work schedule, letters to herself, a notebook she kept during the process and social media accounts. The Diamondback corroborated facts with 11 people, including Blair’s friends and university officials.

University officials explained that business days refer to when this university is open for business. The Diamondback counted these days from when Blair reported her case on Nov. 23, 2015 until she was notified of the final sanction on July 28, 2016 during a meeting with officials.